(2015/5775)

Kol Torah is enormously proud to present a landmark article written by TABC alumni Reuven Herzog '13 and Benjy Koslowe '13, themselves former Kol Torah editors-in-chief. This article was originally delivered as a Shiur at TABC's summer of 2014 Tanach Kollel.

The article presents an intriguing solution to a very well-known issue regarding the compatibility of Chazal's Seder Olam and the commonly accepted historic chronology. Although dozens of articles address this issue, we believe that this article is the best article written on this subject published to date.

This article is based on a series of Shiurim given by Rav Menachem Leibtag at Yeshivat Har Etzion.

I. Introduction

The Hebrew calendar counts the current year as 5775 Anno Mundi[1]. However, many adherents to this calendar may not realize that this year stems from Seder Olam Rabbah, a late Tannaitic work. Detailing important dates and years in Jewish history, Seder Olam establishes a timeline from Adam HaRishon to the end of the Bar Kochba revolt, and it became the ubiquitous dating convention in the Jewish community around the turn of the second millennium CE.

A challenge regarding the Hebrew calendar is that the year 5775 may not be so precise. Seder Olam records that the time between the destructions of the two Batei Mikdash lasted 490 years. However, secular history records that the Churban of the first Beit HaMikdash took place in 586 BCE, and that the Churban of the second Beit HaMikdash occurred in 70 CE; this leaves us with a period of 655 years[2]. Thus, there is a discrepancy of 165 years between Seder Olam and secular history!

The “missing years” are a puzzling element of the Jewish Mesorah. They beg the question of what happened to them and whether Seder Olam was intended to be a definitive history or something else entirely.

In this article, we intend to follow Seder Olam’s chronology and explain how it reaches its conclusions, using an internally consistent methodology. Beyond this, we hope to demonstrate how Seder Olam’s inconsistency with outside sources is not a flaw; rather, it serves a tremendous purpose in the Rabbinic period.

II. Seder Olam’s Count

Seder Olam Rabbah is a Tannaitic work generally attributed to the mid-2nd century Tanna Rabi Yosi ben Chalafta. A Midrashic commentary on Jewish history, it chronicles and exegetes the stories of Tanach and a little beyond, using the historical narratives as a springboard for Chazal’s teachings and messages, similar to other Midreshei Aggadah. In fact, Seder Olam can be thought of as similar to the Midrash Rabbah collection, a “History Rabbah[3],” in that its goal is not to explicitly comment on historical facts, but rather to use stories as an educational tool.

In building its timeline, Seder Olam uses two primary sources, both stemming from the Tanach. The first and dominant source is explicit references from the books of Tanach to specific years and periods of time, combined via simple arithmetic intuition. These references are plentiful and clear enough to write the timeline almost entirely, from Adam HaRishon to the Churban of the first Beit HaMikdash. (The dating of Malchut Yehudah is slightly cloudier; we will deal with this later.) The second source is implicit references and inferences used to fill in the gaps where Tanach is more ambiguous. These are primarily used in the works post-Churban HaBayit, where dates of certain events are given, but there are no large blocks of time recorded.

II-A. From Adam HaRishon until the Beit HaMikdash’s Destruction

The first section of the timeline is incredibly easy to construct, taken almost directly from lists found in Sefer BeReishit. After the conclusion of the Gan Eden narratives there is a list of Adam’s descendants, including how long they lived, and more significantly how old they were when the next child on the list was born. As an example (BeReishit 5:12-14):

“VaYechi Keinan Shiv’im Shanah VaYoled Et Mahalaleil. VaYechi Keinan Acharei Holido Et Mahalaleil Arba’im Shanah UShemoneh Mei’ot Shanah VaYoled Banim UVanot. VaYihyu Kol Yemei Keinan Eser Shanim UTsha Mei’ot Shanah VaYamot.”

“And Keinan lived 70 years, and he gave birth to Mahalaleil. And Keinan lived 840 years after giving birth to Mahalaleil, and he gave birth to many children. And all the days of Keinan were 910 years, and he died.”

The only relevant information for us in this paragraph is how long Keinan lived before the birth of his son; everything afterwards is overlap and therefore does not help to create a contiguous timeline.

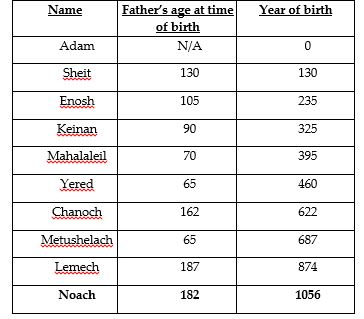

Such Pesukim are repeated almost verbatim for the entire line of Adam to Noach, ten generations in all (plus the birth of Noach’s children, the eleventh generation). The result of this timeline is a simple calculation of dates for when each person was born:

A very similar list exists in Perek 11, after the Mabul and Migdal Bavel stories, listing the generations from Sheim to Avraham:

After Avraham’s birth, the points of reference in the Torah are more spread out, and often these references describe large blocks of time rather than individual lifespans. The Torah informs us that Avraham was 100 years old when Yitzchak was born (21:5). After Yitzchak’s birth, there are 400 years until Yetziat Mitzrayim. This is based on Seder Olam’s derivation from the Berit Bein HaBetarim that the 400 years of Avraham’s descendants dwelling in a foreign country begin with the birth of Yitzchak[6]. Thus, Yetziat Mitzrayim took place in year 2448 of Seder Olam.

The next block of time is from Yetziat Mitzrayim until the start of construction of the first Beit HaMikdash, a period Sefer Melachim informs us was 480 years (Melachim I 6:1). We can therefore establish that the Beit HaMikdash began its time in year 2928 of Seder Olam.

In order to calculate the duration of the first Beit HaMikdash, Sefer Melachim records the length of each king’s reign. Adding up the reigns of the kings from Shlomo – in whose fourth year as king the Beit HaMikdash’s existence began – to Tzidkiyahu – in whose reign it was destroyed – we have a total of 433 years[7]. However, because the dating system then was focused on the king and not on an absolute, continuous calendar (as we mentioned above), the final partial year of a king’s rule was counted as a full year, and the rest of that year was also considered to be a full year for the next king. Therefore, we can conclude that there was an extra year of overlap recorded for each king. Accounting for the 19 rulers7 and therefore 19 years of overlap, our total reduces to 414 years. We also need to remember that construction began in the fourth year of Shlomo’s reign. We therefore remove four years to give the final count of 410 years for which the first Beit HaMikdash stood. Thus, the Beit HaMikdash was destroyed in year 3338.

II-B. Galut Bavel and the Second Beit HaMikdash

After the Beit HaMikdash’s destruction, the records become much less comprehensive. There is no book that details a continuous history or provides dates in a larger context. All of the post-Churban Sifrei Tanach (like many of their earlier counterparts) give exclusively regnal dates. Nothing informs us how long a king ruled, or even who directly succeeded him.

When the second Beit HaMikdash begins to be built in the second year of the Persian king Daryavesh, Zecharyah retrospectively references a period of 70 years (Zecharyah 1:12). This refers to the destruction of the Beit HaMikdash and Yerushalayim and the subsequent exile (with no mention of Babylonian rule, as this prophecy comes many years after the Babylonian empire fell)[9]. Therefore, the second year of Daryavesh and the beginning of the construction of the second Beit HaMikdash was in year 3338+70=3408 of Seder Olam. Construction took four years (Ezra 6:15), finishing in Daryavesh’s sixth year, year 3412.

From this point on everything becomes much murkier. There are no “anchor dates” like in Yirmiyahu 25[10]. The few dates mentioned after the construction of the second Beit HaMikdash are only in reference to the king of the time, and we do not even know for sure the order of succession, much less for how long each Persian king ruled.

The latest date recorded in Tanach about Daryavesh is his sixth year, the year in which the second Beit HaMikdash was completed. The next date we have is that of Ezra’s Aliyah to Eretz Yisrael, in the seventh year of king Artachshasta (Ezra 7:7). Seder Olam assumes that these two names refer to the same king, so these two events are only one year apart[11]. The last reference we have to Daryavesh/Artachshasta is during the governorship of Nechemyah, in his 32nd year (Nechemyah Perek 12). This can be calculated to be year 3438 of Seder Olam.

This is the latest concrete date that can be found in Tanach. However, a hint to later events can be found in a vision of Daniel. In Perakim 10 and 11, in the third year of Koresh[12], Daniel receives a long, prophetic, colorful, and obscure description of much of the future political history from an angel. At the beginning of the history the angel states, “Hinei Od Sheloshah Melachim Omedim LeParas,” “Behold, three more kings will stand for Persia” (Daniel 11:2); the fourth of the line[13] will be tremendously rich, and he will be conquered by an extremely powerful king of Greece[14].Seder Olam assumes this king to be Alexander the Great, and thus the king succeeding Daryavesh/Artachshasta is Alexander. In addition, Seder Olam twice references that the Persians ruled over Israel for 52 years, which leads to the deduction that Daryavesh/Artachshasta ruled for 36 years. (This extra time is hinted at in Sefer Nechemyah, where Nechemyah mentions that he was in Persia during Artachshasta’s 32nd year, and he took leave to return to Israel after a long period of time (Nechemyah 13:6).) Koresh took control in 3390; hence, Alexander’s reign over the Persian Empire begins in year 3442 of Seder Olam.

Seder Olam follows Alexander’s reign with a summary of the rulership until the Second Beit HaMikdash’s destruction (and then to the Bar Kochba (alt. Ben Koziba) Revolt) in a succinct teaching of Rabi Yosi[15]: 34 years of Persian rule during the existence of the Beit HaMikdash, 180 years of Greek rule, 103 years of the Chashmona’i dynasty, and 103 years of the Herodian dynasty – totaling 420 years. Bar Kochba’s rebellion was 52 years later.

In the second installment of this essay, we will bring light to issues that arise when comparing Seder Olam’s account of Bayit Sheini chronology with the conventional account of history. We will then hopefully explain how Seder Olam’s account consistently employs the methodology of Chazal to successfully arrive at its conclusions, regardless of outside chronologies.

[1] Lit: Year After Creation. This title is slightly misleading, as Seder Olam begins its chronology with Adam HaRishon and makes no mention of Beri’at HaOlam.

[2] The Gregorian calendar does not include a year 0; year 1 BCE is succeeded immediately by year 1 CE.

[3] Though this would be an apt title for the work, its real title does not denote any connection. The “Rabbah” suffix merely means “big,” distinguishing it from a later chronological work also titled Seder Olam (Zuta).

[4] The Pesukim are not entirely clear here, stating only that Noach was 500 years old when he gave birth to Sheim, Cham, and Yefet. However, in the list from Sheim to Avraham, Arpachshad is stated as being born when Sheim was 100 years old, two years after the Mabul (11:10); therefore, we can deduce that Sheim was born 98 years before the Mabul. The Mabul is said to have been when Noach was 600 years old (7:6), in year 1656; thus, Sheim was born in year 1558.

[5] BeReishit 11:27 states that Terach was 70 years old when he gave birth to Avraham, Nachor, and Haran. It is assumed that Avraham was the oldest brother.

[6] This Derashah is based on the usage of the word “Zera,” offspring, in the Berit (15:13): “Yado’a Teida Ki Geir Yihyeh Zar’acha BeEretz Lo Lahem VaAvadum VeInu Otam Arba Mei’ot Shanah,” “Know well that your offspringwill be strangers in a land that is not theirs, and they will enslave them and torture them four hundred years.” This “Zera” is identified by Seder Olam to match with the Pasuk (21:12), “Ki VeYitzchak Yikarei Lecha Zara,” “For in Yitzchak offspring will be called for you.”

[7] Yeho’achaz and Yehoyachin each ruled for three months, and are not even given credit for an entire year.

[8] The chronology in this table is based on a simple read of Sefer Melachim. The chronology is actually more complicated, but this is beyond the scope of this paper. For further reading, see Edwin Thiele’s The Mysterious Numbers of the Hebrew Kings (1st ed.; New York: Macmillan, 1951).

[9] Zecharyah’s reference is not explicitly about the Beit HaMikdash’s destruction, but from context it is clear that he is referring to the destruction of the Temple, Yerushalayim, and all of Yehudah.

[10] See section IV (Editor’s Note: This will appear in next week’s installment).

[11] Seder Olam uses the ambiguous language of “Hu Koresh Hu Daryavesh Hu Artachshasta” to show that sometimes multiple names refer to the same king. The Gra explains this specific reference to be that Daryavesh is named as Koresh, the “Meshiach Hashem,” by Yeshayahu; Daryavesh is awarded these extra titles because he rebuilt the Beit HaMikdash. (This association of Koresh and Daryavesh might be another element of Chazal’s “hiding” of the disappointing Shivat Tziyon-era Navi at the end of Sefer Yeshayahu. By identifying “Koresh,” who is prophesied to rebuild the Beit HaMikdash, as Daryavesh, who actually did, the author removes the problem of a false prophecy. See section V-B for a further explanation of the “hidden Navi.”)

Interestingly, the Gra writes that there were three separate kings of Persia: Koresh, Daryavesh, and Artachshasta. However, he makes no mention of Achashveirosh, whom Seder Olam explicitly includes, and makes no attempt to identify him with one of the three aforementioned kings! Perhaps the Gra means only that all three of these kings, though Midrashically identified as one by Seder Olam, are separate rulers in their own right, in addition to Achashveirosh. This would pose a problem, though, with Daniel’s vision (found in Perakim 10-11 of Sefer Daniel) of the four Persian kings (including Daryavesh HaMadi).

[12] The vision begins in Perek 10 and continues in Perek 11, according to the explanation of Da’at Mikra.

[13] Presumably this includes a king before Koresh, so the fourth king in total is the third remaining. Perhaps this earlier king refers to Daryavesh HaMadi, who conquered Bavel for Persia. (Daryavesh HaMadi’s identity itself is very unclear; perhaps this is a reference to the general Gobryas who governed over Bavel for a few weeks after conquering it.) The result is that the four kings are Daryavesh HaMadi, Koresh, Achashveirosh, and Daryavesh/Artachshasta.

[14] A similar vision, though less detailed, can be found in Perek 8 of Daniel. Seder Olam cites Pesukim from both visions.

[15] The fact that this history is entirely Tannaitic and not derived from Tanach is incredibly significant. After the mention of Alexander, Seder Olam writes, “Ad Kan Hayu Nevi’im Mitnab’im BeRuach HaKodesh; MiKan VeEilach Hat Oznecha UShma Divrei Chachamim,” “Until here Nevi’im would prophesize with Divine spirit; from here and onward listen to the words of the Sages.” This marks the end of the period of Nevu’ah and a monumental transition in the nature of Judaism. The short section following even has the feel of an appendix to the primary history, that which is relevant to Tanach.